This approach enables earlier diagnoses of neurodegenerative diseases as well as providing insight into how and why the diseases start and how to interrupt them, and helping researchers identify new treatment modalities. Sergott and his team are also reaching across the breadth of Jefferson via exciting partnerships with psychiatry, cardiology, cardiac surgery, neurosurgery, and genetics. “We want to be ahead of the disease and not let the disease get ahead of the patients,” he says. “I believe we have started a platform that will go all throughout the University.”

“Neuro-ophthalmology has often been intriguing and very enchanting, because we could tell through the examination of the eye what might be happening in the brain or the spinal cord,” he says. “This window to the brain has now become even larger with recent technologies. There was disease there, and we couldn’t see it, but today, retinal imaging is remarkable. There are new ways to noninvasively and painlessly image the retina and optic nerve like we couldn’t do before. And it has allowed us to make the invisible visible.”

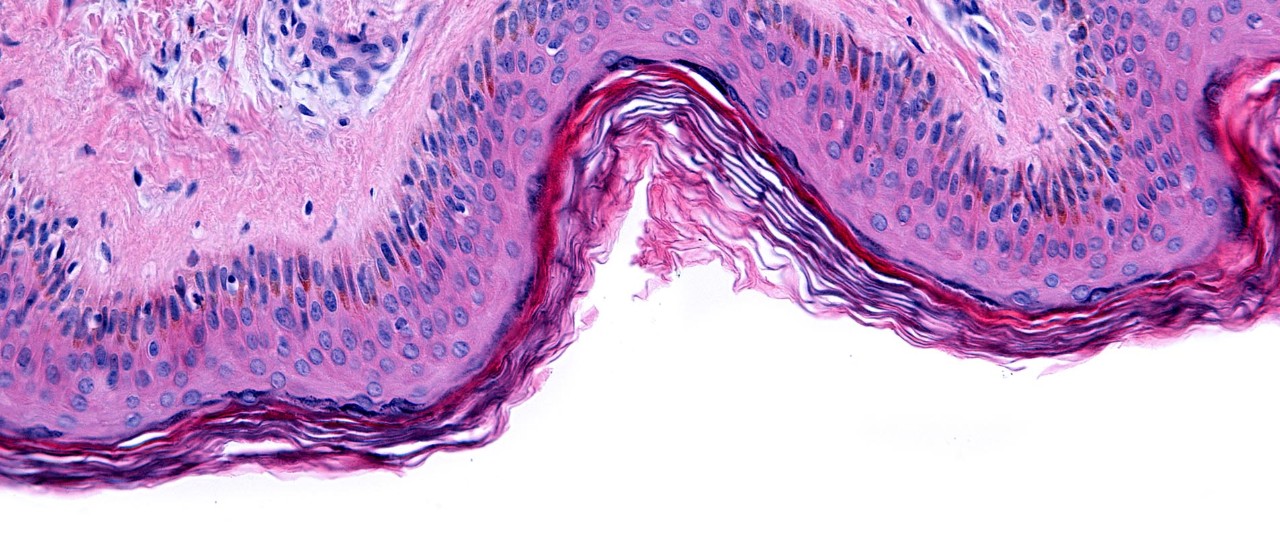

While it’s impossible to biopsy the brain or the spinal cord without doing damage, thanks to the evolution of basic research over the last three to five years, scientists can take samples from skin, urine, or blood; process and culture them in the laboratory; and from there, grow retinas and parts of the brain that function like biopsied tissue, maintaining all the properties of when they were harvested.

They are also evaluating the mitochondrial function within the retina using 3D, 3-nanometer resolution electron microscopy and fluorescent lifetime imaging microscopy and then correlating these findings with tissue specimens.

“The work we’re doing now with fluorescent lifetime imaging ophthalmoscopy, also called FLIO, enables us to study the metabolism of the retina in real time painlessly and noninvasively,” Sergott says. “We utilize two electron microscopes that enable us to correlate these findings with what happens in human tissue, and we can get down to structural, ultramicroscopic details.”

When describing the success of the Annesley Center, Sergott credits the convergence of his collaborations with Jefferson colleagues across many disciplines, partnerships with medical technology, research, industry, and regulatory agencies, and support from Jefferson leadership and philanthropists Margaret and Richard Hayne.

“I’ve been in medicine a long time,” he shares. “It’s rare that you have this coalition of people coming together with their own expertise, their own critical thinking, all the way from leadership through philanthropy through science. It doesn’t happen often. There is continuing inspiration — that sometimes turns into aspiration — from seeing patients who we have not been able to help.”

When asked to reflect on his legacy and what powers him forward, Sergott says, “First, I took good care of patients. Second, we added some new knowledge to neurology, ophthalmology, and neuro-ophthalmology that enables us to diagnose and treat disease sooner and improve the quality of life for those who are either genetically disposed to these diseases or, unfortunately, acquired them. Part of that legacy too is that this goes on and the journey doesn’t stop with me.”